The history of Tamil journalism is a long and interesting one. While the propagation of religion was primarily the focus of early Tamil magazines (the first one being the eponymous Tamil Magazine which was brought out by the Religious Tract Society in 1831), it changed over a period of time to serve other objectives such as dissemination of knowledge on literature, science, art, culture etc. The pioneer in this regard was the ‘Dinavarthamani’, which was founded in 1855 and was edited by Father Percival. This piece is about one such magazine of general interest, the Viveka Chintamani which was founded in 1892 by a man who is not much spoken about today for his contribution to the world of Tamil journalism, CV Swaminatha Iyer.

He was born in 1863 in Tiruvaiyaru. Nothing much is known about his family except that it had once been a wealthy one whose fortunes had dwindled over a period of time. His father Venkatarama Iyer however ensured that the family circumstances did not stand in the way of his son’s education, which was completed at Kumbakonam.

Swaminatha Iyer’s tryst with journalism came about quite as a matter of chance. While on a visit to Madras in 1885, he came into contact with G Subramania Iyer, the proprietor of The Hindu, who had started the Swadesamitran three years earlier. With the job of running two newspapers proving to be an arduous one, Subramania Iyer was on the lookout for a person who would take care of the fledgling Swadesamitran. The mantle fell on Swaminatha Iyer, thus marking the beginning of a long journey in the world of journalism. Though Subramania Iyer remained the publisher and editor in name, it was Swaminatha Iyer who ran the show, as several accounts of the life of G Subramania Iyer and the early years of the Swadesamitran record. Swaminatha Iyer’s stint at Swadesamitran lasted for a decade. This experience would come in handy when he would go on bring out the Viveka Chintamani.

It was around this time that several associations such as the Triplicane Literary Society and the Madras Hindu Reform Association were founded to promote public discussions and thought on various socio-political issues prevailing at that point of time. In the early 1880s, G Subramania Iyer and M Veeraraghavachariar founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge on the lines of the eponymous organisation that had been founded in London in 1826. The organisation mainly aimed at the creation of political awareness and knowledge amongst the masses. It however did not last for long as dwindling interest finally led to its closure in the 1890s. The idea did not die, for it served as an inspiration to Swaminatha Iyer to start an organisation on similar lines. Thus, was born the Diffusion of Knowledge Agency on March 1st, 1892, its primary objective being promotion of the habit of reading amongst the vast rural population and creating opportunities for learning. In order to carry out its objectives, Swaminatha Iyer began a monthly magazine, Viveka Chintamani, the first issue coming out in May 1892.

Viveka Chintamani was 32 pages in size and had articles on a variety of topics such as science, moral instruction for students, current affairs etc. As early as the second issue, it had a page exclusively for children, probably the first magazine to do so. It also had a separate section for women. The magazine had several significant achievements, particularly in the field of Tamil fiction to its credit. It serialised Kamalambal Charithram by the young BR Rajam Aiyar, which was perhaps only the third novel in Tamil. The story ran for two years, between February 1893 and January 1895. The following year, it was brought out as a book by CV Swaminatha Iyer. It serialised the early episodes of A Madhaviah’s work Savithri Charithram in 1895, before it was stopped abruptly for reasons unknown. The magazine would later carry his work Muthumeenakshi. It also carried book reviews and short stories of authors such as Milton, Rabindranath Tagore etc translated into Tamil.

Viveka Chintamani also actively promoted the study of the Tamil language. It ran several articles on its literary and grammatical aspects. ‘Parithimaar Kalaignar’ VG Surayanarayana Sastriar wrote a series on the life of many Tamil poets, which was released as a compilation titled ‘Tamilppulavar Charithram’ after his death in 1903.

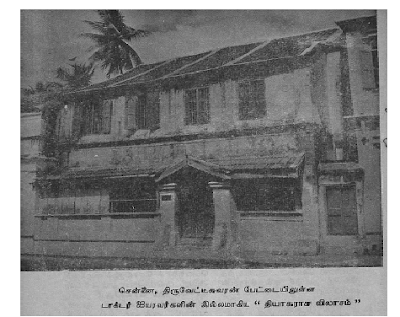

Very interestingly, the magazine came in two editions, a thick paper one for ‘schools, patrons, reading rooms and circulating libraries’ and a thin paper one for the masses. The office, which was in Sydoji Lane, Triplicane was shifted the Swaminatha Iyer’s residence Lalitalaya in Adam Street in Mylapore around 1908 or so.

CV Swaminatha Iyer was a man of several other interesting facets. He was a highly spiritual personality. An active practitioner of Kundalini Yoga, he was also a Srividya Upasaka, who took on the monastic name of Satyananda. He founded the Ananda Mission in 1903 in Chidambaram, whose aim was the ‘the propagation of Truth and Knowledge as the way to Health, Happiness and Life through self-help, self-control and self-culture’. It sought to work for the ‘uplift of humanity by uplifting of human thought above the considerations of the lower self’. He believed staunchly in the sovereignty of the rule of the King Emperor and led the initiative to appeal for the renaming of Black Town as George Town following the Coronation Durbar in 1905. The name change was announced the following year. His ardent support of the sovereignty however did not stand in the way of his taking an active part in the proceedings of the case that followed the Arbuthnot Bank crash in 1906. He had lost nearly Rs 20000 in the crash. It was following his petition that Justice Boddam, a preference shareholder (and therefore an interested party) of one of Arbuthnot & Co’s main assets, the shares of Arbuthnot Industrials Limited recused himself as the Insolvency Commissioner.

Approaching the age of sixty, Swaminatha Iyer handed over the reign of Viveka Chintamani to his elder son, Sadanand soon after the completion of its Silver Jubilee year in 1917. It however did not last for much longer, winding up in the 1920s. Sadanand was however on his way to becoming a legend in his own right in the field of journalism. He founded the nationalistic Free Press Journal Agency in Bombay and ran the eponymous paper in the 1930s. He bought the Indian Express from Dr P Varadarajulu Naidu in 1933 and ran it for a while, before it was taken over by Ramnath Goenka. He was also one of the seven founding shareholders of the Press Trust of India. Swaminatha Iyer’s younger son, Dr S Natarajan (more popularly known by his pen name, Najan) too would carry on his father’s legacy. A renowned Srividya Upasaka, he wrote more than 100 books in his lifetime on diverse topics.

Lalitalaya’s tryst with journalism continues till date, with Dr Natarajan’s son running a publishing unit from the redeveloped premises.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

1. Various issues of Viveka Chintamani

2. Indhiya Viduthalaikku mundhaiya Tamizh idhazhgal, (Part 1), E Sundaramoorthy and Arasu M.R, International Institute of Tamil Studies, 1998.

He was born in 1863 in Tiruvaiyaru. Nothing much is known about his family except that it had once been a wealthy one whose fortunes had dwindled over a period of time. His father Venkatarama Iyer however ensured that the family circumstances did not stand in the way of his son’s education, which was completed at Kumbakonam.

Swaminatha Iyer’s tryst with journalism came about quite as a matter of chance. While on a visit to Madras in 1885, he came into contact with G Subramania Iyer, the proprietor of The Hindu, who had started the Swadesamitran three years earlier. With the job of running two newspapers proving to be an arduous one, Subramania Iyer was on the lookout for a person who would take care of the fledgling Swadesamitran. The mantle fell on Swaminatha Iyer, thus marking the beginning of a long journey in the world of journalism. Though Subramania Iyer remained the publisher and editor in name, it was Swaminatha Iyer who ran the show, as several accounts of the life of G Subramania Iyer and the early years of the Swadesamitran record. Swaminatha Iyer’s stint at Swadesamitran lasted for a decade. This experience would come in handy when he would go on bring out the Viveka Chintamani.

It was around this time that several associations such as the Triplicane Literary Society and the Madras Hindu Reform Association were founded to promote public discussions and thought on various socio-political issues prevailing at that point of time. In the early 1880s, G Subramania Iyer and M Veeraraghavachariar founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge on the lines of the eponymous organisation that had been founded in London in 1826. The organisation mainly aimed at the creation of political awareness and knowledge amongst the masses. It however did not last for long as dwindling interest finally led to its closure in the 1890s. The idea did not die, for it served as an inspiration to Swaminatha Iyer to start an organisation on similar lines. Thus, was born the Diffusion of Knowledge Agency on March 1st, 1892, its primary objective being promotion of the habit of reading amongst the vast rural population and creating opportunities for learning. In order to carry out its objectives, Swaminatha Iyer began a monthly magazine, Viveka Chintamani, the first issue coming out in May 1892.

Viveka Chintamani was 32 pages in size and had articles on a variety of topics such as science, moral instruction for students, current affairs etc. As early as the second issue, it had a page exclusively for children, probably the first magazine to do so. It also had a separate section for women. The magazine had several significant achievements, particularly in the field of Tamil fiction to its credit. It serialised Kamalambal Charithram by the young BR Rajam Aiyar, which was perhaps only the third novel in Tamil. The story ran for two years, between February 1893 and January 1895. The following year, it was brought out as a book by CV Swaminatha Iyer. It serialised the early episodes of A Madhaviah’s work Savithri Charithram in 1895, before it was stopped abruptly for reasons unknown. The magazine would later carry his work Muthumeenakshi. It also carried book reviews and short stories of authors such as Milton, Rabindranath Tagore etc translated into Tamil.

Viveka Chintamani also actively promoted the study of the Tamil language. It ran several articles on its literary and grammatical aspects. ‘Parithimaar Kalaignar’ VG Surayanarayana Sastriar wrote a series on the life of many Tamil poets, which was released as a compilation titled ‘Tamilppulavar Charithram’ after his death in 1903.

Very interestingly, the magazine came in two editions, a thick paper one for ‘schools, patrons, reading rooms and circulating libraries’ and a thin paper one for the masses. The office, which was in Sydoji Lane, Triplicane was shifted the Swaminatha Iyer’s residence Lalitalaya in Adam Street in Mylapore around 1908 or so.

CV Swaminatha Iyer was a man of several other interesting facets. He was a highly spiritual personality. An active practitioner of Kundalini Yoga, he was also a Srividya Upasaka, who took on the monastic name of Satyananda. He founded the Ananda Mission in 1903 in Chidambaram, whose aim was the ‘the propagation of Truth and Knowledge as the way to Health, Happiness and Life through self-help, self-control and self-culture’. It sought to work for the ‘uplift of humanity by uplifting of human thought above the considerations of the lower self’. He believed staunchly in the sovereignty of the rule of the King Emperor and led the initiative to appeal for the renaming of Black Town as George Town following the Coronation Durbar in 1905. The name change was announced the following year. His ardent support of the sovereignty however did not stand in the way of his taking an active part in the proceedings of the case that followed the Arbuthnot Bank crash in 1906. He had lost nearly Rs 20000 in the crash. It was following his petition that Justice Boddam, a preference shareholder (and therefore an interested party) of one of Arbuthnot & Co’s main assets, the shares of Arbuthnot Industrials Limited recused himself as the Insolvency Commissioner.

Approaching the age of sixty, Swaminatha Iyer handed over the reign of Viveka Chintamani to his elder son, Sadanand soon after the completion of its Silver Jubilee year in 1917. It however did not last for much longer, winding up in the 1920s. Sadanand was however on his way to becoming a legend in his own right in the field of journalism. He founded the nationalistic Free Press Journal Agency in Bombay and ran the eponymous paper in the 1930s. He bought the Indian Express from Dr P Varadarajulu Naidu in 1933 and ran it for a while, before it was taken over by Ramnath Goenka. He was also one of the seven founding shareholders of the Press Trust of India. Swaminatha Iyer’s younger son, Dr S Natarajan (more popularly known by his pen name, Najan) too would carry on his father’s legacy. A renowned Srividya Upasaka, he wrote more than 100 books in his lifetime on diverse topics.

Lalitalaya’s tryst with journalism continues till date, with Dr Natarajan’s son running a publishing unit from the redeveloped premises.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

1. Various issues of Viveka Chintamani

2. Indhiya Viduthalaikku mundhaiya Tamizh idhazhgal, (Part 1), E Sundaramoorthy and Arasu M.R, International Institute of Tamil Studies, 1998.